Background

With the power to harness the body’s own immune cells to target and destroy cancer cells at tumor sites, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell immunotherapy has transformed cancer treatment over the past decade. By combining adoptive cell transfer with sophisticated engineering, CAR T-cell therapy enables the harvesting and modification of patient T cells to express synthetic constructs that recognize specific tumor-associated antigens.

Although the biochemical and immunobiological factors underlying T cell function, such as receptor signaling and cytokine activation, are now well characterized, most research has overlooked an equally essential component of T cell antitumor activity: mechanical signaling. T cells do not just recognize antigens biochemically; they also feel them mechanically. When a T cell encounters a target, it senses mechanical forces that help it decide whether to activate, form an immunological synapse, or initiate killing. This process, mechanotransduction, converts physical cues into biochemical responses.

Importantly, impaired mechanics can contribute to dysfunctional tumor cell killing and suboptimal clinical responses. Understanding and controlling T cell mechanics could therefore advance therapeutic outcomes of immunotherapy.

In their review “Advances in ligand-based surface engineering strategies for fine-tuning T cell mechanotransduction toward efficient immunotherapy” published in the October 7, 2025 issue of Biophysical Journal, Luu and colleagues address how the mechanics of the signal can be as important as its chemistry. As summarized below, the authors explore ligand-based surface engineering strategies to modulate T cell mechanotransduction and anticancer responses.

The mechanics behind activation: How T cells feel

Luu et al. first illustrate how mechanotransduction underlies every step of T cell target recognition. When a T cell receptor (TCR) binds to an antigen, this bond is strengthened under the right amount of force. These force-sensitive catch-slip bonds allow T cells to distinguish real threats from harmless signals. In short, slip bonds weaken when tension increases, leading to minimal T cell activation, while catch bonds strengthen under applied mechanical force and are associated with agonist peptides that trigger full T cell activation. Recent research showed that T cells can transmit 12–19 pN of tensile force during activation, with a single TCR requiring ~12 pN to reach its activation threshold. Because CAR-T cells rely on synthetic receptors, they often need much higher forces (60–100 pN) to achieve comparable activation. This insight underscores how mechanical tuning could directly influence therapeutic outcomes.

The authors also emphasize that ligand geometry and spacing, which are biophysical cues, play critical roles in TCR activation. Clustered ligands elicit stronger forces that promote TCR aggregation for more effective T cell activation, whereas widely spaced ligands lead to weaker force transmission, low cell spreading, and weaker T cell activation. Thus, the geometric arrangement and mobility of ligands influence both the force threshold and the efficiency of force transmission during T cell activation, which are fundamental elements of T cell mechanotransduction.

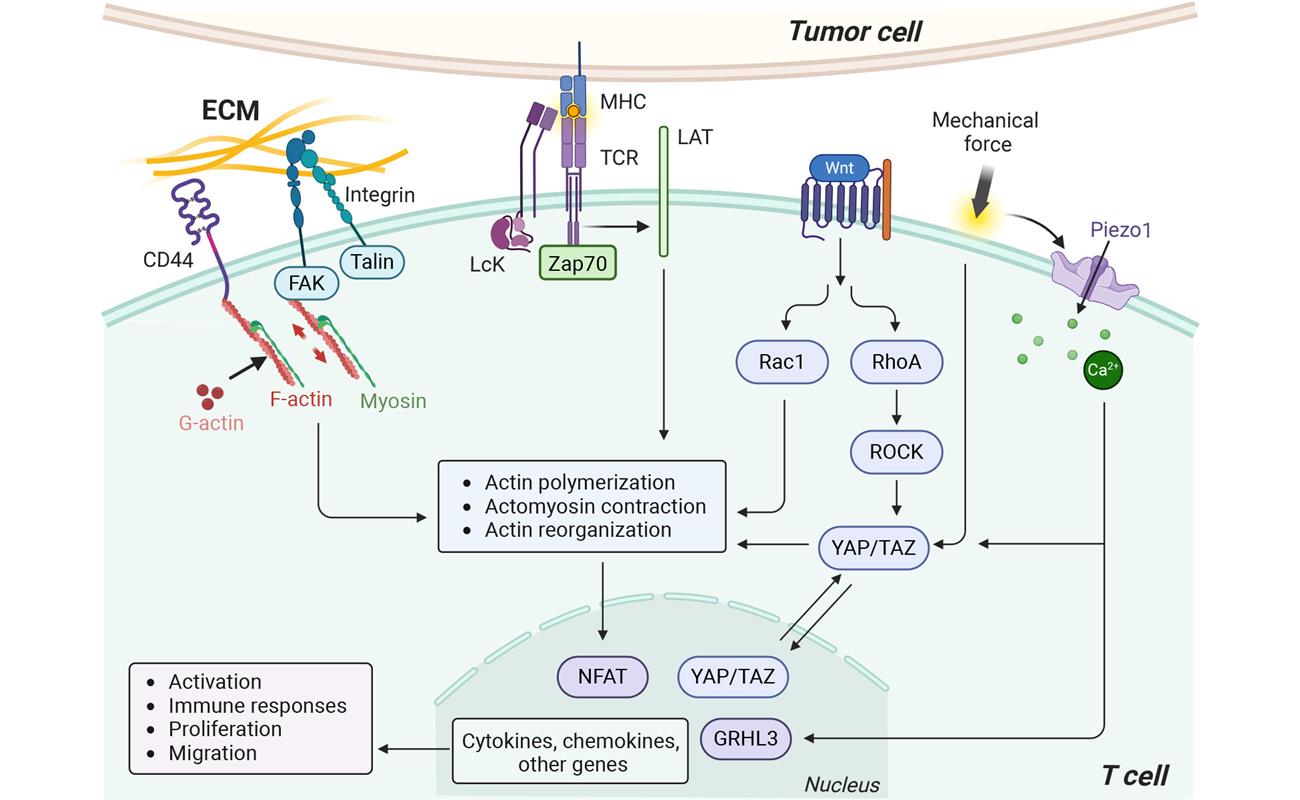

The immune handshake: from cytoskeletal remodeling to tailored gene expression

Once activated, T cells form the immunological synapse. This dynamic contact zone, essentially a “molecular handshake,” is powered by intense remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton and membrane tension. Proteins that link the plasma membrane to the actin cytoskeleton are deactivated during engagement with antigens, reducing membrane tension and facilitating T cell ligation. This process activates mechanotransduction cascades, in which signaling molecules like small GTPases coordinate actomyosin contractility and help T cell spreading on the target surface.

At the cell surface, T cell mechanosensing is regulated by adhesion molecules and ion channels. Integrins help detect substrate stiffness, promote F-actin polymerization, lamellipodia formation, and migration during immune responses. Another family of molecules, the mechanosensitive Piezo1 ion channels, sense membrane curvature and tension in a calcium-dependent manner to regulate TCR activation.

Downstream, mechanosensitive transcriptional coactivators like YAP/TAZ respond to changes in cytoskeletal tension and substrate stiffness, tuning T cell activity by translating mechanics into gene-expression changes. Upregulation of YAP serves as a feedback mechanism to prevent excessive T cell activation, while YAP deletion enhances cytokine production and tumor growth.

Altogether, Luu and colleagues emphasize how this immune “handshake”—bridging mechanics and gene regulation—fine-tunes how T cells activate, exert force, and sustain their antitumor responses (Figure 1). Precise control of these mechanical pathways offers an opportunity for research to enhance T cell function and possibly improve cancer immunotherapy.

Figure 1: Mechanotransduction pathways in T cell. It mainly involves TCR activation, mechanosensitive channels (e.g., Piezo1, TRPV4), adhesion molecules (e.g., integrins, CD44), the downstream cytoskeletal (e.g., RhoA/ROCK, Rac1) and transcriptional regulators (e.g., Wnt, YAP/TAZ). Figure reproduced from Luu et al.

Nanoengineering surfaces

Luu et al. highlight how researchers are now applying these insights to optimize T cell activation, namely using nanoengineering approaches. Existing techniques include nanolithography, nanoarrays, and DNA-based nanostructures that allow for precise control of ligand density, spacing, geometrical arrangement, and ligand mobility—key parameters to modulate T cell activation.

For instance, one study using a single-molecule array platform showed that clusters of ~37 ligands optimize TCR activation, whereas larger clusters actually reduce efficiency. This study also showed that spacing plays a far more dominant role than density: T cells respond optimally when TCR ligands are spaced 13–23 nm apart and held at an intermembrane distance of ~10–13 nm. Too much distance weakens signaling, whereas tight clustering strengthens it. These findings are reinforced by other studies using DNA-based surface engineering approaches.

Importantly, making ligands mobile by using dynamic ligand presentation systems can allow tunable ligand binding and thereby better mimic receptor-ligand interactions. Such systems enable controlled, tunable, and reversible interactions, further enhancing T cell activation by promoting receptor clustering and signal amplification. Because CARs require much higher activation forces (60–100 pN) than TCRs, Luu and colleagues highlight that such systems could be engineered to match distinct force requirements and binding affinities, tailoring mechanical forces to receptor type.

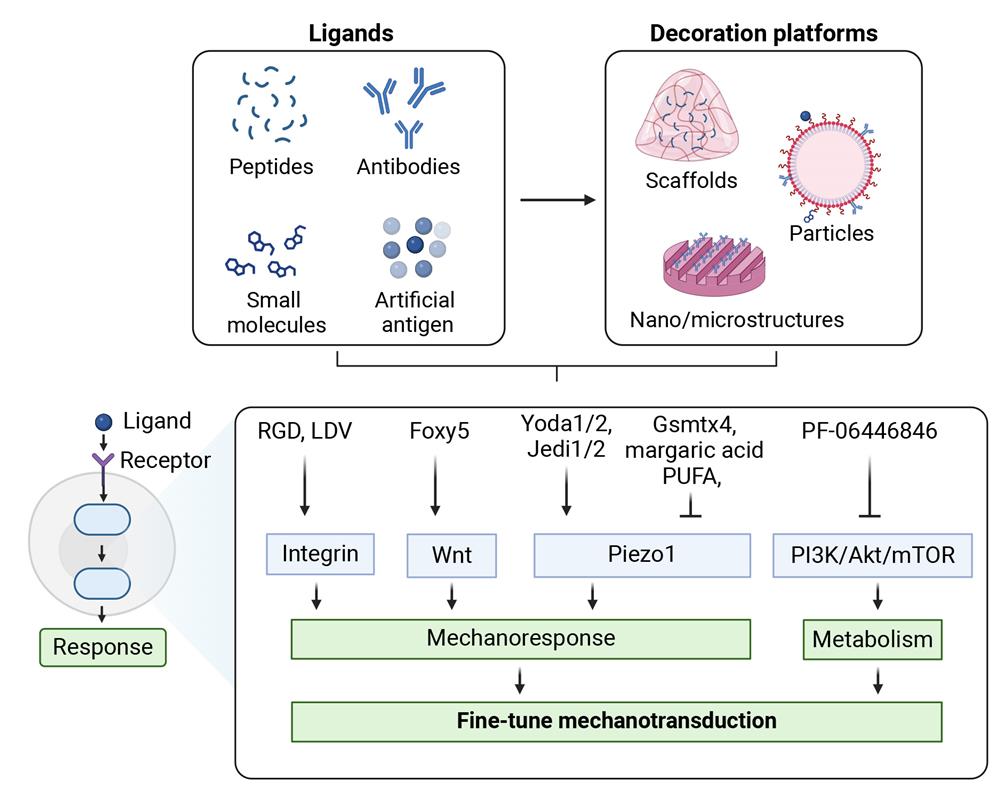

Surface decoration: Tuning T cell mechanics through ligand design

Building on the insights mentioned above, Luu et al. describe how surface-decorated ligands have been engineered to mimic (and even enhance) the mechanical and chemical cues that T cells encounter during activation. These new platforms include biomaterial-based approaches like 2D scaffolds and 3D hydrogels and particle-based approaches, each designed to enable researchers to more effectively modulate T cell mechanotransduction (Figure 2).

One major strategy includes surface decoration of peptides that target cell adhesion molecules, such as functionalized Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) or Leu-Asp-Val (LDV) sequences that bind integrin to promote cell adhesion, focal adhesion assembly, and cytoskeleton organization. In CAR-T cells, for instance, an LDV-conjugated functional immune cell matrix scaffold was shown to accelerate proliferation by enhancing integrin-mediated mechanotransduction.

Another emerging strategy uses synthetic peptides, whose sequence can be easily modulated to regulate T cell activation. For instance, the Foxy5 peptide, a short sequence derived from the Wnt5a ligand, can be functionalized on polydimethylsiloxane substrates to enhance noncanonical Wnt signaling via the RhoA-ROCK pathway. This leads to strengthened actomyosin contractility and enhanced activation of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. When co-presented with RGD, Foxy5 can provide a synergistic effect on different mechanosignaling pathways.

Similarly, Jagged-1, which activates Notch signaling, was used to demonstrate the potential of hydrogel-mediated presentation of mechanosensitive motifs. In T cells, Notch activation enhances antitumor responses and the memory capacity of cytotoxic T cells. Upon antigen recognition in new synthetic Notch-CAR T cells, mechanical forces trigger gene expression through receptor cleavage, demonstrating how force can be translated into gene regulation.

Other strategies have focused on targeting mechanosensitive ion channels, especially Piezo1. Luu et al. note that although small molecules such as Yoda1/2 and Jedi1/2 can chemically activate Piezo1, they have not yet been designed as targeting ligands nor decorated on substrates. The authors propose that future studies could immobilize these ligands on nano-engineered and smart biomaterial-based substrates, ensuring specific targeting of mechanotransduction while enabling cells to experience mechanical stimulation. Importantly, regulating T cell activation in vivo through mechanical stimulation could offer a powerful alternative to conventional biochemical approaches, potentially reducing off-target effects.

Figure 2: Surface engineering of mechanomodulatory ligands for fine-tuning T cell mechanotransduction toward efficient immunotherapy. Figure reproduced from Luu et al.

Looking ahead

The current review by Luu and colleagues provides a comprehensive overview of emerging nanoengineered and biomaterial-based platforms that integrate immunomodulatory ligands to tailor T cell responses. Their work underscores how surface-decorated mechanomodulatory ligands offer a powerful strategy to precisely tune T cell behavior by linking mechanical cues to immune function.

While these approaches are promising, several challenges remain before these tools can be translated to the clinical setting. Many of these platforms are still optimized for in vitro use only, where mechanical parameters can be (relatively easily) controlled. Reproducing these forces in a complex and heterogeneous mechanical environment like that of living tissue will undeniably present a significant hurdle. Even translating quantitative force thresholds, such as the 60-100 pN for CAR-T cell activation, clinically for human therapy, represents a significant challenge.

Despite these limitations, the convergence of mechanobiology, synthetic biology, and surface engineering strategies promises significant advances. As this field continues to grow, harnessing (mechanical) principles—alongside biochemical ones—may help pave the way toward more effective and safer immunotherapies.